本日は日刊スゴい人!が創刊し、記念すべき500回目。

500回目を迎えることができたのもひとえに読者の皆様の応援のおかげです。ありがとうございます。

その、500回目にふさわしいスゴい人!が本日登場する。

生まれは東京の魚屋。

幼少の頃より親からの厳しい教育と深い愛情を受け、挫折をしない考え方が身についたという。

父からの教えを忠実に守り、落語の世界でも、映画やテレビの中でも大活躍を納めた。

父親から受けついだ『日本人の心』とは?

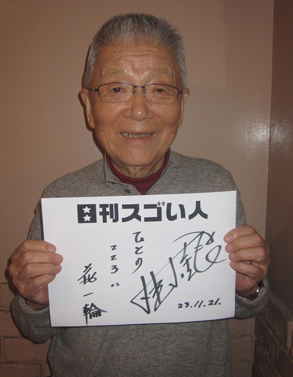

さあ・・・桂小金治師匠の登場です!

「今日の幸せは父のおかげ」

家は魚屋をしていた。10歳の時に親父に呼ばれて、「お前も年が2桁になった。いつまでも親に頼るな。いずれ自分の力で生きていかなくてはならない時が来る。その準備のために働け。働くということは、自分の体を動かして傍を楽にすることだ。」

坊主頭に鉢巻を巻いて、10歳の時から働いたんだよ。

終戦後、あたりは焼け野原で仕事が無い。父親に相談をしたら、「死んだらいいだろう。」の一言。自分で生きるのに、自分で考えないなんて馬鹿だとその時思ったね。

父親は寄席が好きでよく寄席につれて行ってもらった。笑っている親父の姿を見るのが好きだった。

それに、父親から3着の着物をもらったので、それを生かそうと新宿末広亭の楽屋を訪ねた。

『人から用事を言いつけられて働くやつは半人前。自分の目で見つけて働くやつが一人前』

と父から教えられていたので、一生懸命働いた。

そうしたら、「よう働くやっちゃ」と当時芸術協会の副会長だった桂小文治師匠が目に留めてくれ、弟子にしてくれました。

父に報告したらお祝いに赤飯を炊いてくれることに。

でも、時は終戦後。米が無いのは知っていた。翌朝目を覚ましたら、茶碗と箸と赤飯があったんです。聞くと、父親が冬の寒い中米屋の前を何件も周ってこぼれている米を拾ってきてくれた。そのご飯を食べながらボロボロ涙が流れた。

私にとって、“草笛”が人生の支えです。子どもの時に友人の家でハーモニカを吹いていて欲しくなり、父にねだりました。父は葉っぱを一枚差し出して、これで吹けというのです。もちろん吹けない。

俺は鳴らせるぞって“ふるさと”を吹いたんです。ビックリしました。「やり方は自分で考えろ」と言われましたが、吹けないので、3日で辞めてしまいました。そうしたら、「辞めたというのは、自分に負けたんだろ?この意気地なし」とハッパを懸けられ、練習を続けたら、音が鳴ったんです。その時の嬉しさと言ったら、言葉では表現できません。

翌朝、枕元にハーモニカがおいてあった。草笛が吹けるようになったら、渡すつもりで4日も前に買ってくれていたそうです。今でもハーモニカを吹くたびに父の優しさを思い出して涙が出ます。

努力までなら誰でもする。そこで辞めたらどんぐりの背比べで終わり。辛抱をして最後には辛抱という棒の上に花が咲くんですね。

落語に取り組む時も、俳優になった時も片時もこのことを忘れたことはありません。

日本の子どもたちに、父から受けついだ日本人の心を伝えていきたいと思います。

??????????

Rakugo is best explained as “sit-down comedy,” as opposed to the “stand-up comedy” popularized in the west. A performer sits on a big cushion, and using only minimal props at hand, tells a long story with an elaborate cast, acting out all of the characters as well as the narrator. The story inevitably has a gag, usually a pun, at the end. Though it was popularized during the Edo Period, it still enjoys a large following today, and many performers, often foreign, offer shows in English across the country.

He was born to a fisherman in Tokyo, brought up in the strictest environment of love. It was this upbringing that has helped him through hard times, he claims. He follows his father’s words to the letter, even while working in the blustering industry of television, film… and rakugo. What is this “Japanese Heart” his father instilled in him so long ago?

Let us introduce you to Mr. Katsura Kokinji, so that he can tell you himself.

“Today’s happiness is thanks to Dad.”

My home was a fishery. When I was ten, my father said to me, “your age is in the double digits. You can’t depend on your parents forever. One day, you’ll have to live by your own hand. Work now, so that you can prepare yourself for it. Working means to move your body, and make things easier for others.” I tied a kerchief around my shaved head, and began to work at ten.

After the war, everything had been burned down, and there was no work. When I asked my father for advice, he could only say, “I suppose it would be best now to die.” I thought how stupid that was, seeing as we were both well and alive. Since my dad liked the theatre, he often bring me along. I loved to see my father laugh.

I had recieved three kimono from my father, so I figured I might as well put them to use, and called upon the Shinjuku Matsuhiro Tei theatre.

“A person who is told what to do is only a half a man. A person who sees what he should do with this own eyes, is a man.”

But this was after the war. I knew there was no food. Yet when I woke the next morning, I saw a chawan bowl and my chopsticks, and sekihan rice. When I asked about it, I found that father had gone out into the cold winter and went to all of the rice dealers, picking up the rice that had been dropped on the ground. Tears flowed from my eyes as I ate that meal.

For me, life had been like a kazoo. I had once seen a harmonica at my friend’s house, and begged and pestered my dad to buy me one. In response, my dad gave me a leaf, and told me to blow that instead. Of course I couldn’t make it sound.

“I can,” replied Dad, and he played the song “Furusato” for me. I was shocked. “Figure out how to do it on your own,” I was told. But after messing around with the leaf for three days and failing, I gave up. Dad teased me. “Giving up means you lost, doesn’t it? Loser.” And so I went back to trying. Eventually I did learn how to do it – to play the leaf just like a kazoo. There are no words to express how pleased I was as my success!

The next morning, the harmonica I had wanted was there on my desk. He had bought it four or five days earlier to present to me when I had taught myself how to play a leaf kazoo. Even today, when I play my harmonica, I cry at remembering my father’s kindness.

Anyone can put in a little effort. But it’s all over when you let yourself hunch over like an acord and give up. There is a saying that “sakura will bloom on the end of a stick with patience.” When I turned to Rakugo, when I became an actor, too, at all times, I never forget that. It is the Japanese heart. I wish I could teach the generation of the future about the grand Japanese heart instilled in me by my own father.

(Translation by Haruka Orth)

タグ:芸能人